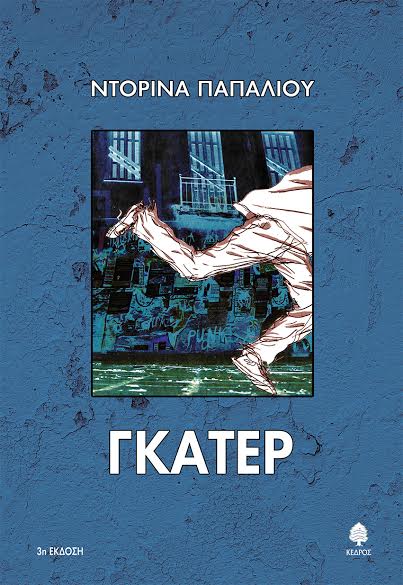

GUTTER

(GUTTER, KEDROS)

Novel, 262 pages

ISBN: 978-960-04-3650-1

Kedros 2007

IBBY AWARD, 2008

Option Agreement for film adaptation, with Argonauts Productions S.A.

What Alex fights for is his right to be himself. But this is not an easy battle to win when being himself means becoming a professional comics artist. Unwilling to submit to the future his narrow minded, condescending and austere father has mapped out for him,- read economics at the London School of Economics and then return to Athens to work for the family business, a factory that manufactures screws-, abandonded by his loving mother who works for an NGO in Mozambique and last but not least, painfuly missing his great love Isabella who left to study abroad, Alex finds emotional support and artistic guidance in his encouraging new mentor, Erikos, a brilliant thirty year old comics artist and owner of a small comics bookstore.

When Erikos, who constantly praises Alex’s talent, talks him into preparing a portofolio of his work to present to the famous American agent who will be giving a talk at the upcoming comics art show in Athens, Alex feels that a real opportunity has finally risen, that his dream of one day becoming an established artist in the tradition of Joe Sacco, Art Spiegelman, Marjarine Satrapi might not be merely utopic. But things take an unexpected turn when late one night, while hanging out in a half lit artsy haunt, packed with people, Alex sketches the face of a man sitting at the corner table.

The man is only a stranger, just another face in the crowd. There is nothing special about him, not at first. Alex sketches him out of habit. He always sketches the people around him, trying to capture grimaces and expressions and attitudes and even feelings, working non stop for his portofolio. But then, when two thugs walk in the café and approach the stranger and drag him out, Alex thinks he sees the outline of a gun sticking out of one of the two thugs belt. Or could he be wrong? The stranger tosses something under the table towards him, his gaze locks with Alex’s. Is he trying to tell him something? Is he being kidnapped, right there, in front of everyone, yet no one is noticing? Or is it just Alex’s wild imagination? Very soon, Alex will realize that in that dark, underground hole, Kylix’s Café, he had unintentionally drawn the first panel of a story that could at any moment break out from the safe haven of his sketchpad and spill out into the real world – his real world – turning it upside down.

Gutter: the word itself in the language of comics is used to define the empty space between two successive story panels, a space that pushes the reader’s imagination to take a cognitive leap and give continuity and meaning to the images.

Praise for Gutter in the Greek press

“Papaliou masterly interweaves the most widely different threads… starting out with the traditional mystery story, where the detective is called upon to fit together the scattered pieces of an initially incomprehensible puzzle, she enters the world of comic superheroes and of graphic novel…while it touches upon teenage literature, featuring complicated and often traumatic family relationships….Beyond its literary intelligence, however, Papaliou’s book stands out for its vivid anthropology: its heroes are compact with integrated personalities, filled with the contrasts, contradictions and conflict befitting their age, gender and social class.” V.Hatzivasileiou, Eleftherotypia

“The portrayal of characters and the unfolding of the plot reveal a masterly hand…multiply stimulating. It features the latest thematic trends (the central character is a young comic artist), impeccable execution (the plot merges seamlessly with the young-adult literature and crime novel genre), ultra-heightened suspense (it holds your interest completely to the last page).” E. Kotzia, Kathimerini

“…when I held the book in my hands and started to read it, I had this feeling, from the very first moment, that here is a story that has riveted my attention. I had the irresistible urge to go on and on.” P. Markaris, Athens Voice

“Papaliou masterly interweaves the parallel, mutually-crossing narrative “steps” of comics-writing with novel-writing, which, to my mind, is what makes her novel so interesting…. Undoubtedly, an exceptionally remarkable and original debut novel.” E. Houzouri, Vivliothiki, Elftherotypia

“Gutter merges crime literature with comics in a genuinely innovative manner…Whether you are a comics fan or not, Dorina Papaliou’s Gutter is a fascinating, remarkably well-structured crime novel, which bridges the gap between the two art forms and serves as an imaginative introduction to comics.” Culture/O Kosmos tou Ependyti, Myrto Tselenti

Articles

(Culture/O Kosmos tou Ependyti)

By Myrto Tselenti

Publication Date: 24-04-2008

Dorina Papaliou’s new book, by Kedros Publishers, is a very special novel- a bridge between comics and literature.

Gutter merges crime literature with comics in a genuinely innovative manner. The main hero, teenager Alexander, is an aspiring comic artist. He is passionate about comics. He acts like a hero coming out of a comic. He is surrounded by them. He talks about comics, mainly with Errikos, his mentor, who also happens to be the owner of a little shop selling collectors’ comics, aptly called “Krazy Kat” (named after a well-known comic strip by George Heriman).

There are numerous references to the ninth art in the book, ranging from design techniques, inking and colouring, to heroes, readers and trends. Already from Chapter 1, famous authors and creators are referred to – Miller, Moore and Gaiman. Moreover, there is a particularly insightful, remarkably realistic outline of the Greek comics scene, featuring the main Athenian comic art festival, gossip and all sorts of references to comics in Greece and abroad today.

There are more references to come as we read on. Dorina Papaliou’s handling of the subject is rather artful. Comics are adequately explained to ensure that the non-expert feels very much at home with them, while sparing the informed reader of superfluous references he already knows about.

This is one of the major achievements of this book. While comic fans find themselves in familiar surroundings right from the start, as if they were in a café with their pals sharing jokes in a language, incomprehensible to the uninitiated, those who look upon the medium with scepticism and prejudice will not feel left out and will have to confront their position. This is done discreetly rather than in an aggressive, conspicuous way. Gutter plays a catalytic role in helping the reader to find his bearings in the realm of the ninth art, seen through the eyes of someone who really loves and understands comics, urging him to reconsider his views on the subject and adopt an open-minded attitude towards them.

Besides the numerous references to comics, what I found most intriguing about Gutter was its structure. The book is closely modelled on the comics style of narration, figuring prominently the stylistic element implied in the title itself.

Mind the Gap

In the beginning of the book, the author explains that the word “gutter” (also used in Greek) is an English technical term used by comic artists to denote the space between two successive panels; it is the gap where the reader has to make a mental leap in order to link consecutive panels. While the word is most often used to refer to a “ditch” or “channel”, it is also used figuratively with respect to the underworld.

The implications of the latter use of the word are clear enough. It relates to the world in which Alexander will be immersed. However, I find the former meaning considerably more intriguing. Apart from winking playfully at the world of comics, this connotation encapsulates the quintessence of what the book is all about. The hero is called upon to do just that: join the fragmented images that he receives one way or another and piece together a story. He has to resolve a mystery by taking leaps of logic to connect the various scattered pieces of information in order to discover the hidden story of a mysterious puzzle. The reader follows the hero’s journey by guessing along with him what’s missing between the various clues that turn up in the story, trying to make sense of the sequence between gutter and image, joining and transforming two unconnected images into a single idea.

Empty space is important in a comic in another way, too. Within a panel in a comic, the space left empty often defines the image not only visually, but also with respect to meaning. It empowers and intensifies the object or scene that it presents, revealing to the reader hidden emotions or thoughts. It is an important element in the functionality of the individual panel, as well as of the whole comic.

Similarly, the absence of Alexander’s mother from the novel helps the reader to reconstruct not only her image and character, but also his entire childhood, his relationship with his mother, her influence over him, as well as the impact of her absence on his family, social environment and himself. Also, the absence of Isabella, the girl he is in love with, helps bring across the fact that to him love is associated with absence and pain. Evidently, it is the absence of the dead from life that urges him to search for their experiences and press on with his adventure.

There are many such instances of parallelism in the book, but I won’t go over all of them here, because I don’t want to spoil the sheer delight of your discovering them for yourselves.

Whether you are a comics fan or not, Dorina Papaliou’s Gutter is a fascinating, remarkably well-structured crime novel, which bridges the gap between the two art forms and serves as an imaginative introduction to comics.

(Athens Voice)

By Thanasis Mylonas

Publication Date: 03-04-2008

The volume of novels of this genre is on the raise. Similarly, the number of Greek publishers turning out crime novels by Greek authors is definitely higher compared to earlier production. Correspondingly, domestic authors in the genre are enjoying a wider popularity among the general public.

By way of comparison, how many reputable Greek crime novelists of the ’50s or ’60s can one mention by name? In all likelihood, just one: Yiannis Maris. “For many years, the genre of crime fiction in Greece had been identified with Yiannis Maris”, Antaios Chrosotomidis comments in the preface to the collection of crime novels Greek Crimes (Kastaniotis Editions).

It wasn’t until many years after the publication of Crime in Kolonaki and Backstage Crime that other crime novelists followed suite, although output was scanty. For instance, Athina Kakouris’ novel The 218 Names was published as early as 1963. However, the genre of crime fiction only became well-established in Greece and gained momentum in the ’90s onwards, through the work of such authors as Petros Markaris, Andreas Apostolidis, Philippos Philippou, Petros Martinidis and others. A typical example is probably the case of Petros Markaris. Several of his books have sold very well, have been reprinted repeatedly in Greece and have been translated into other languages (German, French and Spanish). Besides, the adventures of commissioner Charitos have even been turned into a popular TV series…

The Greek crime novel reached its current peak in popularity when it stepped – apparently intentionally – into the mainstream that had established itself on an international scale in recent years.

Proponents of this trend claim that crime novel is the most suitable literary platform for addressing the issues confronting modern societies. In the preface to the book Greek Crimes, Antaios Chrysostomidis points out that “A new generation of authors has emerged, who should not perhaps be destined to become crime novelists. They are a generation of intellectual and leftist authors who redraw the map and reset priorities”.

Political corruption, the Press as a form of authority, the totalitarian regime, the problems facing the unemployed, homeless and refugees – these are the most pressing issues that are taken up in some of the greatest and most successful novels by “veterans” in the genre: Markaris’ The Late-night News, Zone Defence, When Che Committed Suicide and Major Shareholder; Martinidis’ Memory Games, Dead for the Second Time and In Succession; Apostolidis’ The Lost Game and Disturbances at Meteora; Philippou’s Death Circle and The Black Hawk e.t.c. Besides, similar thematic content is popular with somewhat modern authors, like Marlena Politopoulou, Argyris Pavliotis, police reporter Kostas Kyriakopoulos, Titina Danelli and others. Other authors go off the beaten track: Dimitris Mamaloukas, who “transcends” the Greek borders in his books; Panagiotis Agapitos, who writes mystery stories set in the Byzantine era; and Dorina Papaliou, who draws her inspiration from the aesthetics of the comics genre. Undoubtedly, the Greek crime novel is blossoming into maturity. Athens Voice has posed the following questions to the masters of the genre:

1. With the notable exception of Yiannis Maris and a few others, the crime novel genre was virtually non-existent until the end of the ’70s. How do you explain that?

2. Nowadays crime novel draws its themes from the social environment and its problems. What is your explanation for this change in attitude?

3. Athens is a city that generously provides authors of the genre with material. To what extent would you say that this can be attributed to the fact that Athens is becoming increasingly multi-cultural? Is it a “ville noir”?

ANDREAS APOSTOLIDIS

It isn’t quite right that crime novel was virtually non-existent before 1970. Actually, in the ’50s and ’60s it was much more widely spread than today. It was popular with the masses through The Mask and Mystery magazines- women’s magazines that featured police novels- and the press that published crime novels in a series of episodes. Magazines were provided with original material by authors like Nikos Marakis and Orfeas Karavias (Felix Kar), with stories by Athina Kakouri, novels by Takis Papageorgiou, on a par with Yiannis Maris, the writer with the top sales record in 20th-century Greece.

There was a sudden change at the end of the ’70s and the genre became extinct in the next two or three years for a number of reasons. First, it never really kept step with current events in the country (political or social) – rather, it hushed things up because of the Civil War and Cold War, except in certain isolated cases (urban districts like Kolonaki and the underworld in Fokionos Negri, which feature in the work of authors like Maris, Marakis and others). Secondly, the advent of television disrupted communication between the genre and its audience. Finally, the censorship imposed by the military junta further restricted the genre’s already limited expression of social realism, creating an aversion to anything that was police-like, while literature with political content went ahead to widespread acclamation. It took 20 years for the situation to be reversed and the genre to be re-established.

It is in this context that I called my first crime novel The Lost Game, which hints at the crime genre of the ’50s and ’60s, setting the story in a block of flats in the upper-end district of Kolonaki, in the early days of the April military coup.

The genre has made its comeback today more as an elitist rather than a folk narrative style. Book binding and mode of distribution have changed beyond recognition. Its relatively mandatory self-reference in the ’90s has given way, in the current decade, to a thematic spectrum that is closer to the genre of social novel, reflecting current events and developments. It is in this context, therefore, that state corruption, immigration, violence and excessive piety are issues that often come under criticism in the genre. The lack of certainty that plagues Marxist and neo-liberal models enhances the tendency for social analysis through the form of the crime novel. It is a widespread European tendency that is also partly domestic. In the USA, however, James Elroy’s noir novel is still the dominant genre.

Athens has undergone major transformations since the ’90s. As regards the police novel, I am of the opinion that it can now claim its own organized underworld (which is the subject of my novel Lobotomy) and city areas populated by immigrants of various ethnical backgrounds. The dual meaning of “stranger” is, by definition, linked to the police novel – criminals and immigrants are as strange to us as we are to them, except if we reverse the narrative perspective, which would result in a new pair of strangers (in Highsmith’s style).

PETROS MARKARIS

Black-and-white categorization in Greece has always flourished and art has been no exception to the rule. Dividing lines still exist, like serious vs. commercial theatre, artistic vs. commercial film production, literature vs. pseudo-literature, serious vs. light music, etc. Within these narrow-minded confines, crime novel fell under pseudo-literature, in line with “light” or “commercial” genres. Of course, other countries, like France and Germany, went through this phase, which was short-lived and blew over much sooner than in Greece, where it lasted much longer.

First of all, let me set the record straight on a common misconception: noir is quite distinct from crime novel; they are two different genres. Now, as for the crime novel veering towards a social thematic content, it must be recalled that the genre of the novel was predominantly social in character until the mid-20th century. After World War II, this trend changed, particularly following the emergence of the “new novel” in France. The novel developed an interest in the face, character and persona, while interest in the social environment declined. These divergent trends created a gap and, over the past few decades, the crime novel has taken on itself the task of bridging this gap. But this has again to do with the fact that the thematic content of the police novel has changed. Today, the genre is more concerned with organized and financial crime, or the involvement of organized crime in politics- namely with political and financial crimes that have become “embedded” in society.

Athens is a metropolis that shares the same features with other major European cities. It has become a stage of criminal activity, like so many other European urban areas, because modern crimes, as described above, thrive in the physical space of a megalopolis. Consequently, the megalopolis has assumed an increasingly important role in crime novel. It no longer simply provides a social environment, but has been cast in a central role in the crime novel. This social phenomenon spawned authors who left their mark on the cities they describe, like Montalban in Barcelona, Rankin in Edinburgh and Paretsky in Chicago.

ATHINA KAKOURI

The genre output was similar to that of any other literary genre and reflected changes in readership.

We should also include in the ranks of Greek crime novelists of the ’50s and ’60s those who wrote novels under pseudonyms (English for the most part) with the action taking place in foreign countries, mainly England and America, because publishers and editors-in-chief believed that only British crime novel sells well.

For instance, in the Tachydromos magazine that published my police stories in the ’60s – those celebrated times when Lena and Giorgos Savvidis ran the business –newly-appointed director Giorgos Roussos asked me to write about murders set in England under an English pseudonym. I refused because, as I explained, I did not know England. However, from a commercial standpoint, he was right, because when, in 1974, Michalis Meimaris, an audacious publisher (Plias Publishing House) released one of my novels, in pocket-size format, the venture flopped.

Therefore, the answer to your question is that conditions in the ’50s and ’60s were improving, but at a very slow pace. The crime novel – like any other novel genre – has always drawn its themes from society. At this point we can recall Gladstone’s celebrated case, when he was once late for a Parliament session because, as he confessed, he had to finish reading The Woman in White, one of Willkie Collins’ crime novels. What’s more, he immediately filed a motion for amendments to the existing legislature, because the woman’s position – as described in the crime novel – was a disgrace for a country like England.

It is then indefensible to argue that crime novelists have just been alerted to their social environment. Naturally, the problems confronting society are not the crime novelist’s main concern; otherwise the crime novel would lose its true identity and become identified with the social, political, psychological e.t.c. novel. The crime novel has its own set of rules. For instance, it is meaningless without a crime, a police officer who won’t excite the reader’s curiosity or won’t challenge him to resolve the crime and find the culprit. These elements are necessary to a lesser of greater extent.

The so-called classic American noir described a certain class of the American society. Similarly, what is known as the atmospheric quality of the British School has been about the English village, university town, London e.t.c. In other words, they are social groups or forces with a beneficial or adverse effect, like the Press, for instance.

The current trend towards the description and attempted analysis of the social environment reminds me of the genre that Simenon cultivated, where the emphasis is shifted from the crime being investigated to the social environment, which is examined in much greater depth. However, if you read Dickens’ The Mystery of Edwin Drood, you will notice that the great master scored high on both counts.

A multicultural society is not a requisite for man to commit a crime. A lot of conditions, however, have changed over the last decades. Until the ’70s, the severity and frequency of crimes was far below today’s norm, which is evident from police reports at the time. The murder cases for an entire year did not exceed 10; the police retrieved, as a rule, stolen property in a few days; while burglaries were rare and bank robbers only showed up in films.

But back then, we had not yet been confronted with the first bunch of Albanians, ex-convicts in their country who were quick to train our budding criminals accordingly; drug trafficking and weapon trade were non-existent; nightclubs were few and far in between, frequented by peace-loving individuals who were fond of singing a song or two; trafficking of women was unthinkable and all of us Greeks were poorer and – necessarily – more virtuous.

After all, the Gospel is right in talking about how difficult it is for the rich to be admitted to paradise…

DORINA PAPALIOU

It could be that in Greece the crime novel was raised to the status of the serious literary genre relatively late. In those days, crime novels surfaced mostly in newspapers, magazines and on the radio and, as a result, they were inevitably more closely associated with popular culture rather than mainstream literature. The reluctance of Greek authors to experiment with the genre could possibly be attributed to the doubts raised about the value of the crime novel. Only a handful of daring individuals took the plunge, like Yannis Maris and Athina Kakouri with their crime stories. We cannot, however, exclude the possibility that the average Greek author is not particularly attracted to the genre.

They say that crime fiction is the new novel commenting on social structures. Indeed, crime novelists tend to project and study social relationships more extensively, rather than limit themselves to the solution of a puzzle of the type “who killed x”. The more interesting the social environment where a police officer, detective or some other character moves in his quest of the truth, the greater the intellectual depth of the novel. Bekas, Maris’ central character, moves in a clearly recognizable Athens of the ’60s, while Charitos, Markaris’ protagonist, is active in contemporary Athens. Greece abounds in problems and the crime novel is an ideal platform for addressing them, as this genre of fiction by nature deals with problems.

People change and cities follow suite. New social phenomena emerge that give rise to new contrasting situations and offer opportunities for new stories. The more multicultural and cosmopolitan Athens becomes, the closer it resembles the model cities of Hammett and Chandler, proponents of the “hard boiled” American noir novel, where corruption permeates everything and criminals are on the loose. Organized crime, which was non-existent in the ’60s, has now become a reality for Greece. It seems to me, though, that despite the changing landscape, Athens remains a very humane city, unlike, lets say, Chicago, during the Prohibition of Alcohol in the 1920s.

PANAGIOTIS AGAPITOS

The necessary urban social conditions for the systematic cultivation of the genre were lacking: megalopolis, social mobility, organized crime, violence. Maris’ storylines reflect this, as they are akin to the corresponding storylines of Greek films: the setting and casting are clearly-cut.

As I see it, the causes of this change of course can be attributed to the great changes brought about by World War II. The collapse of moral and social values, the presence of a policy of social criticism that is steadily gaining momentum, the financial reconstruction and the diffusion of money have modified the parameters that determine the qualities of crime myth-making. In Greece, crime fiction follows the general trend, which was, however, introduced into the country with some delay.

Why only Athens? Every major city can provide both the material and the setting. Obviously, the role of a multicultural environment is important, and so is the city’s cosmopolitan character. To an author like me, who writes crime novels set in 9th century Byzantium, the corresponding Byzantine city (e.g. Thessaloniki in The Copper Eye) is just as rich in material as a contemporary city. But in mythmaking, cities remain “fictitious”, no matter how “realistic” they may seem. As regards the essence of narrative direction, Athens in 2000 and Constantinople in 840 are the “same”, in the sense that they are both well-suited to provide for the needs of the authors.

TITINA DANELLI

I should think that the main reason for this delay is the political, financial and social conditions in Greece. Metaxas assumed office in ’36! Then there was the war, occupation, civil war, poverty, unemployment and urbanization. And then we landed with the insanity of April 21, 1967. It was a nightmare that did not last one night, but went on and on for seven consecutive years. It is then hardly surprising that the advent of crime fiction in Greece was delayed. Who would decide to write about imaginary crimes, when crimes were actually committed at their doorstep on a daily basis?

As a rule, literature draws its themes from social problems and when these change, so do the authors’ speculations and reflections. In America, Hammett’s old but excellent clichés were at last replaced. Besides, in England they don’t write in the style of Graham Greene, while in France the know-all, but wonderful Maigret has become outdated. Fortunately, in Italy, the shadow of Leonardo Sciascia hangs heavily over the authors, some of whom even aspire to carry his school into the future; because he did establish his own school. Everything is changing- whether this is for the better or for worse, nobody knows. We, Greeks, have changed, too, as citizens and authors. You cannot let life walk on by while you look on out of your own private glass world.

Athens has become a “ville noir”. Not because of its multicultural character. Our own people have seen to that. The indiscriminate building activity, air pollution, noise pollution and kitsch turned it into “ville noir”. The sight of monster-buildings makes you feel sick. But poverty, zero social security for the homeless and drug users, let alone the stranded illegal immigrants, is food for thought for the author.

DIMITRIS MAMALOUKAS

I don’t agree. The ’50s and ’60s are the “golden age” of the Greek crime novel, sometimes truly remarkable and sometimes just plain flabby or mediocre. Strangely enough, this occurs when the nation goes through the intensely adverse – and essentially illiberal – post civil war climate, while crime fiction supposedly comes to fruition in liberal ambience. Some of the authors in that period (at random order) are Y. Maris, N. Marakis, A. Markaki, L. Kakouris, N. Foskolos, G. Ioannidis, N. Routsos and G. Korinis. The genre (which obviously falls under pseudo-literature) goes into decline at the end of the ’70s, with only a handful of important authors (F. Ladis, T. Danelli, Ph. Philippou, P. Aristeidis e.t.c.) re-emerging forcefully in the ’90s.

Because of the tension and qualitative “upgrade” in the character of social issues, including globalization, authoritarianism in various forms, organized crime, the deterioration (and entanglement) of institutions and of all sorts of authority, a new “proletarization” of population groups arises. In this world, crime fiction plays a catalytic role, serving, among others, as “resistance culture”. Consequently, the genre becomes, I believe, one of the most versatile implements in the author’s hands for recording (and interpreting, depending on his keenness of insight and judgement) social, and hence, political conventions.

Crime fiction is predominately the literary genre about urban communities, where class conflicts are accentuated and related social manifestations are often explosive and extremely violent. Over the last two decades, Athens (a particularly attractive and interesting metropolis) has been developing at a fast rate “exploitable” features, similar to those of other “classic” cities in the mythology of crime fiction, like immigration, “ghettos”, marginalization, widespread corruption etc. But let’s be honest and admit that Athens was a “ville noir” already in the days of Y. Maris…

(LIFO)

By Giorgos Karouzakis

Publication date:06-03-2008

Gutter, Dorina Papaliou’s debut novel, is living proof that there can be a fascinating crime fiction novel in Greek, featuring a tight plot, convincing, true-to-life characters and mounting suspense, which is not discharged exclusively on a simple search of themurderer.

What is Gutter? How would you describe it in brief?

Gutter is a crime fiction novel that goes beyond the confines of the genre. The fact that the hero of the story is neither a police officer nor a professional detective, but a young comic artist, adds another dimension to the story, which has to do with the hero’s personal life: a young man’s passionate attempt to achieve his life’s objective. Through his eyes, the novel explores a young man’s fears and doubts about how to proceed in his life.

How did you come up with the idea of combining in your novel a true-bred crime story with the visual and elliptical technique of narrating normally found in comics?

This novel was born out of my love for comics and crime fiction. Theidea was actually sparked from the word “gutter”. The word gutter isused as a technical term in the jargon of comic artists – in Greek as well – to refer to the gap, the empty space between panels, where the reader joins mentally one picture with another. In English, though, the term has more connotations. It is used to describe a trough or channel, but also the underworld. It is in this word, with its various meanings, that I found the plot of Gutter and thus used it as the title of my book. The hero of Gutter, Alexander, is an ambitious young man who sketches incessantly panels in a story that this time unfolds not only on paper, as a comic, but in real life as well. Alexander gets engrossed in his search for the truth behind a crime that he happened to witness and gets into trouble with the underworld.

Why did you cast an eighteen-year old boy in the role of a detective solving a crime?

From the very beginning I had a clear picture of the crime that was to be committed in the book. However, it took me quite some time to decide on the hero of the story, the person who would eventually solve it. I knew that I wanted him to be a comic artist, but I wasn’t sure what his personal life would have to be so as to justify his wild decision to become involved in the investigation of a violent crime. In the face of Alexander, an impulsive, solitary, angry young man, coming from a broken family, who is just entering manhood, I saw the character I was looking for. His teenage passion to be himself, his obsession to sketch incessantly and his eagerness to prove to his social environment that his life’s objective is worthwhile, gave me the opportunity to work out the story in two retro-fed levels. I wanted the hero’s personal story and the plot of the crime novel to be directly connected. Forthis reason, the solution to the mystery, which I am not going to reveal here, served not only to shed light on the mystery, but also to justify Alexander’s objective in life.

There is an interesting twist in the story which is related to the difficulty that even contemporary, apparently liberal parents have in understanding their children’s deep-seated wishes andaspirations. What social or psychological stereotypes support this communication gap?

In Greece, when there is an existing family business (as in Alexander’s case), whatever its nature or level of income, it is almost self-evident that this is where the children will also have to work. This obsession with continuity is widely manifested in Greece. A lot of children grow up in an environment that expects and requires of them to follow the family business tradition. As for the psychological stereotypes that support the communication gap, I should think that it is the deep-seated concern of most parents that their grown-up children get a job in the first instance and become financially independent. Children of an inquisitive mind or possessing a strong, creative nature, have always been a source of grave concern for many parents.

The murderers in your story do not come from the so-called underworld, but are mostly members of the scientific community. What are the implications of this choice?

This choice is clearly in keeping with scripts one often comes across incomics featuring superheroes. The psycho, unscrupulous, brutal criminal scientist who is capable of annihilating half the planet in order to serve his purposes is a favourite “bad guy” in comics. On the other hand, this book belongs to the genre of crime fiction, which has its own set of rules as well as liberties… I believe that the plot should also conform to the rationale of the genre it serves.

I find Gutter’s Athens extremely charming and dark. What appeals to you most about Athens? Why is your story set in these downtown districts?

Athens is a city that looks so very different from one building block to the other that it never fails to fascinate you. When Alexander disappears into the night, in the area under Theatre Square and finally reappears on the run in Athinas Street, only to end up in Adrianou Street, next to the Ancient Agora, he feels as if a few building blocks have taken him across two worlds.

Publishing Trends Magazine

Publication Date: March 2008

Across the Mediterranean, but worlds away, Greek author Dorina Papaliou recently debuted her first novel, Gutter. In this gripping thriller, Alexander, a high-school student and aspiring comic book artist, finds himself in real danger after inadvertently sketching a crime scene. When the young hero decides to investigate it, he discovers a trail that leads to dubious medical experiments, a double murder and, needless to say, a whole lot of trouble. Cleverly bringing together elements of a traditional mystery with the melodrama of comic book plotlines, Papaliou introduces Greek readers to the realm of graphic novels without any graphics. Though quite a comic aficionado herself (in addition to being married to one—Papaliou’s husband, Apostolos Doxiadis, will have his own graphic novel, Logicomix, published next year by Bloomsbury USA/UK), Papaliou recognizes that some of her Greek readers might not be ready to fully transport themselves to the world of comics, just quite yet. In a recent article, the author told Kathimerini English Edition, “Lots of people still believe [comics] are trashy”. It is those sceptics Papaliou seeks to educate through her meta-comic, which alludes to some of her personal favourites, such as Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, each of which is rooted more in politics and history than superheroes.

While so far there has been only one (notably glowing) review to date in the major daily newspaper Eleftherotypia, there is already a considerable amount of buzz surrounding the novel. Many are noting that the nature of the story appeals to both young readers and adults alike. Additionally, in a very unusual occurrence in Greece, it has already been optioned for a film by a Greek film director. So it seems that while the country may not be ready for comics, it may be getting a head start on the comic book movie craze.

2008 Market Partners International, Inc. 232 Madison Avenue #1400, New York, NY 10016

www.publishingtrends.com

(Athens Voice)

By Petros Markaris

Publication Date: 21-02-08

Gutter is an English term in the jargon of comic artists also used in Greek to denote the space between two successive panels, where the reader has to join mentally one panel to the other. The same word in English means channel, ditch, as well as the underworld.

Dorina Papaliou’s novel makes a fascinating read. This qualifying statement is made by an author who, because of the very nature of the genre he pursues, has developed a perversion for fascinating stories. He feels that a story is meaningless without it. Crime fiction is invariably built on a fascinating storyline. Without it, it is not worth reading. And so, when I held the book in my hands and started to read it, I had this feeling, from the very first moment, that I have to do with a story that has riveted my attention. I had the irresistible urge to go on and on.

Gutter is the story of Alexander, a young man who leaves school, reaches his final year of an international school, following the IB program and gets ready, acting on his father’s orders, to study at the London School of Economics. But economics is not his thing. What he really wants is to become a comic artist, to tell stories through this art form. He is a very solitary child and lonely, too, because neither parent is at his side. His father is at work and when he comes home he argues or fights with his son. His mother is not around; she works for a non-governmental organization and is currently away in a Third World country.

The novel starts to unfold gradually. Moment after moment, page after page, it becomes increasingly fascinating and mysterious, all the more so, as its hero is drawn into the world of a frightful crime. The novel slowly discovers, reveals a whole world, a whole story. I won’t give it away. But I will tell you that this road to the end, the unfolding of the story, is solidly built and of great interest.

Another aspect of the book that I found particularly appealing was its characters. I have already mentioned Alexander, but for me the two most fascinating characters in this novel are the parents. We don’t see the mother at all, while we see the father once or twice in passing, arguing with his son. The rendering of these characters in their absence is so complete that it constitutes a truly remarkable achievement for a first-time novelist.

Admittedly, it is extremely difficult to describe so convincingly and vividly two characters that remain unseen. I was really impressed. The fact that this description is so convincing and vivid is reflected, to a large extent, on Alexander’s character and reactions, as well as on the way he withdraws into himself more and more, entrenching the issues that really matter to him.

As both parents are absent, two representatives have been assigned in their place and entrusted with the child’s upbringing. This is a fine subject. The mother is represented by Mrs Koula, the domestic help, acting as a liaison between Alexander and his mother who is in a faraway place. She gives Alexander affection, acting in essence as his governess. The father’s representative is his secretary. She makes the phone calls and watches over him. Standing in for his father, she is, naturally, the strict member of the family.

It is, up to a point, through these representatives, a very conventional family. The substitution of one character for another is an excellent novelty. Alexander is opposed to all this. Because of his young age, he tends to looku pon things his way, invariably from the perspective of design and picture. It’s not only that the novel is based on comics, but also that it is in itself a very vivid reference to them.

Personally speaking, I am extremely intrigued by the connection between novel and comics, the two types of narration contained in the novel. All in all, the novel is very good and makes an excellent read.

(Eleutheros Typos tis Kyriakis)

By Areti Daradimou

Publication date: 03-02-2008

The author explains how she was initiated into comics, voices the opinion that contemporary crime novel should do more than just solve riddles and expresses her intention to follow up her first attempt.

Gutter, published by Kedros Publishers, is Dorina Papaliou’s debut crime novel. Her journey into writing began with children’s literature and she has already published four illustrated books in the genre. To do her justice, however, we must refer to her university thesis that servedas the lead-in to writing and research, in her truly outstanding work on Karaghiozis and Shadow Theatre (CD-ROM Karaghiozis: The Magic of Shadow Theatre). Besides, research is one of the author’s strong points, since Gutter may well be regarded as a comprehensive study of the Greek comic genre and its representatives.

Gutter seems to bridge the gap between children’s and adult literature. Do you perceive this book as your introduction into “adult” literature?

While I was writing Gutter, I didn’t have any particular audience in mind. The book belongs to but is not bound to the crime novel genre. As its hero is a passionate 18-year-oldaspiring comic artist, the book further explores the anxieties of a young man to make it in life.

What caught your attention about the relatively closed community of the Greek comics that made you place your heroin their world?

I’ve been reading comics since I was very young, but I discovered Alexander’s world gradually, as I was pressing on with the writing. It was him who drew me into his world. I went to comic art festivals and shows, I looked around several Athenian comic bookstores and talked with people in the field. I wanted to get a feel for the ambience in the story.

Why did you choose a hero at such a young age and not a tough police officer, which is the norm?

In this book, I tried to combine my love for comics with crime literature. The story is intimately linked with the personality of the young comic artist. It is his ability to sketch and see the world in his own particular way that turns him into a key witness of a crime. His persistence to faithfully reproduce on paper the expression of the man who was the victim ofthe crime scene, hoping that in this way he will understand some hidden secret, leads him to an obsession that soon gets him entangled in the victim’s story.

It seems as if there are two levels of narration in the book. One is the plot of the crime novel and the other isan account of the hero’s ascension to manhood. Was it difficult to strike abalance between the two?

What I was hoping to achieve was that these parallel narratives were interconnected, the one affecting the other. In other words, I wanted developments in the hero’s private life to influence the course of his crime investigation and vice versa. I didn’t want the hero in his capacity as a comicartist and the complications in his private life to be reduced to a simple background. That was quite difficult to do, which is why it took me two years to do the writing for Gutter- outlining, and writing and re-writing many scenes.

What are the difficulties in a crime novel? How does the author handle the clichés of the genre?

A crime novel always involves a crime, which, eventually, will have to be resolved in order to spare the reader of disappointment. For me, the difficultyis not so much in setting up the crime and its resolution, namely, setting up the framework in which the central character, the police or detective, will operate to solve the case, but providing the reader with appropriate information so that his interest in the story will extend beyond the crime. Literary critic Edmund Wilson condemns crime novels in a celebrated article, whose title encapsulates the essence of his criticism: “Who cares who killed Roger Acroyd?”. And yet, his condemnation hints at a suggestion forthe benefit of the genre: the contemporary crime novel genre should not remainwithin the narrow confines of crime solving, piecing together a well thought-out puzzle, which, once completed, leaves the reader with a void. Instead, it should engage the reader with other information, especially regarding the characters. Nowadays, more and more authors in this genre like, for instance, Dona Leon and Petros Markaris, write novels that highlight other dimensions, social as well as psychological.

Gutter looks as if it is the first novel of a potential series of the genre. Are you contemplating another novel starring Alexander Damianos?

I wouldn’t want that. I would like to remember Alexander as the solitary, creative, young boy, whose passion for sketching led him, at somepoint in his life, in the gutter of a horrible crime. However, I intend to press on with the crime novel genre.

(www.mosaiko.gr )

Date of Publication: 21-01-08

Gutter, Dorina Papaliou’s latest crime novel, introduces a new form of crime storyline written from the perspective of the young hero. Who’s that hero? It’s a young cartoon strip designer who is incapable of sorting out his relations either with his parents or with his girlfriend. Does it sound familiar? It does, indeed. Gutter’s pages reflect life and the worries that befall young people. This is rendered admirably through the novel’s remarkable plot, which will certainly appeal to all ages. Mosaiko.gr had the opportunity to interview Gutter’s author and find out more about the writing of the book, the selective influences – from Matt Groening and Hergé to Balzac – as well as her unusualcourses of study in the USA and her plans for the future.

Dorina Papaliou presented Gutter at Papasotiriou Bookshop in Athens, on January 30.

To what extent does Gutter’s subject matter relate to your personal experiences and challenges?

Gutter was an attempt to bring together my love for comics with crime novels. The hero is a young comic artist who is obsessed with his art and makes sketches all the time. Because of a sketch he makes and his acute perceptiveness, he is suddenly witness to a crime. And then, he gradually becomes involved in a dangerous search for the truth of a complex story. Of course, none of these events actually happened. In any novel, however, the characters and storyline serve as a platform for the author to express his feelings, personal experiences and ideas.

The images in Gutter abound in intense, moving feelings. Which artists have influenced you? What are your favourite comics and which authors or artists do you hold dear?

I grew up reading all of Hergé’s books time and again – I was already a Tintin fan at the age of 10. As for the contemporary comic, I admire Art Spiegelman’s Maus, Roz Chast’s comic strips and many other comic artists, from Robert Crumb and Harvey Pekar to Alan Moore, Henry Miller, Neil Gaiman, Matt Groening, Posy Simmons, Sacco and Satrapi.

I should think that two of my favourite novels are Balzac’s Lost Illusions and Le Carré’s The Spy who came in from the Cold.

Would you say that the “graphic novel” is a literary genre that can be more than a trend and become something more permanent? What exactly is the “graphic novel”? How would you categorize Gutter?

What today is termed “graphic novel” abroad, is a new trend in novel writing cast in comics format. Whether it will end up as a comic orliterary genre, it is too early to say. One thing is certain: comics in general gradually become available outside their narrow confines in special bookshops. Many of the titles that I mentioned earlier can be found today in downtown bookshops. Of course, Gutter is not agraphic novel but, because of the peculiarity of its central character, it makes numerous references to the world of comics in general as well as the contemporary Athenian stage.

What would you say is Gutter’s readership?

I wouldn’t limit the scope of Gutter’sreadership. First of all, Gutter is acrime novel. The fact that the central character in the novel happens to be a young man who aspires to achieve his life’s objectives through passion and perseverance, might appeal to a fairly young audience. To the best of my knowledge, however, it is the first Greek novel featuring a comic designer.

How did you decide to write children’s books?

Children’s books were the outcome of a long period of study centred on the art of oral narration, which paved the way originally for my book Listen to a Story: The Traditional Art of Oral Narrative and its Revival Today, (Akritas Publishing House) and, later on, the CD-ROM “Karaghiozis: The Magic of Shadow Theatre” (Kastaniotis Editions). Both works are, in a sense, the outcome of my studies in social anthropology. The reason why I wanted to write for children was my interest in telling stories that can get across to the written word as many elements from the oral narration as possible, regarding the stories themselves and the style of narration. Besides, children are a real audience and a truly strict judge. Have you ever tried reading aloud a book toa child who doesn’t like it or is bored? I should think it is an impossible task…

What would you say are the most pressing problems young Greeks are facing today?

I went to Brown University with a burning passion to study Biology, which I did until I was halfway through my second year, when it dawned on me that I was off course. Then, I managed to turn my studies around, getting a degree in History, while I attended lessons in art direction for the cinema, script-writing and creative writing. I don’t know where else I could have managed to bring about this change in my study plans.

What’s the next piece of work you have been working on?

I have just uploaded a complete website about the Greek Shadow Theatre (www.greekshadows.com) and, of course, I am working on a new novel.

(Vogue)

by Natalia Iordanou-Fourli

Publication Date: 1-2-2008

I walked in her studio: music was streaming from the speakers of the PC and the smell of paper from shelves packed with books filled the room. Figures from the Greek and Indonesian shadow theatre, an Indian “pad” and old photos on the walls from horse riding contests define the angles of her personal stage set. A champion until the year she went to the U.S. to study and gave up the sport, in 1990, Dorina was voted the best female athlete of the last 30 years in horse riding by top journalists in sport coverage.

Parallel to her studies in History at Brown University, Dorina attended classes in art direction and script-writing. “Among others, I was particularly interested in the cinema in those years. I grew up with a mother who was a film director and a father who was a Greek film producer. I was perhaps destined to search for something in this field, even if only tentatively”. Then, she followed a postgraduate course in Social Anthropology at Cambridge University, where the art of oral narration had a marked impact on her. Soon, she published her first book Listen to a Story: The Traditional Art of Oral Narrative and its Revival Today (Akritas) and, later, the CD-ROM Karaghiozis: The Magic of Shadow Theatre (Kastaniotis Editions), as well as several children’s books. “I started out with an interest in oral tradition, exploring traditional storytellers– and then moved on to the Karaghiozis players of the shadow theatre”. Dorina has uploaded a complete website about Shadow Theatre, which can be found at the url www.greekshadows.com, whereas Gutter (Kedros Publishers), her debut novel, has recently come out. She says that “If there is one thing that I’ve most certainly learned from storytellers, it’s that I am always anxious to keep up my audience’s interest”. However, it was her love for comics and the crime fiction that eventually led her to Gutter.

Gutter is a novel of suspense, but also of internal quest. The book follows the rules of the genre of crime fiction, but also tries to tell the story of a young man who passionately struggles to achieve his life’s objective. The hero of the story, a young comic artist, unwittingly bears witness to a crime scene which he happens to have sketched. His drawing gets him involved in the solving of a crime, a search for the truth… In the comics jargon, and as a technical term used by Greek artists, “gutter” is a word that defines a passage, the gap between two successive pictures, the space where the reader can join mentally one picture to another. This term, however, takes on a metaphorical meaning in the story.

Dorina lives in Athens with her husband, author Apostolos Doxiadis, and their three children – in a house without a TV. Her motto on writing is “Work, work and again work…” and if she had to choose two novels that she would like to have written, they would be Balzac’s Lost Illusions and and Le Carre’s The Spy who Came In from the Cold. In answer to the question regarding her opinion of the situation in contemporary Athens, she says that “If I were writing comics with superheroes, I would say that our city urgently needs a uperhero to ‘get her straight’ in every aspect”.

(Herald Tribune – Kathimerini English Edition)

By Vivienne Nilan

Publication Date: 17-01-2008

Gutter is the term comic book artists use to denote the space between two successive panels in a comic. And it is the apt title of an engaging new novel by Dorina Papaliou (Kedros Publishers), in which an aspiring artist risks getting lost in the gutter when his skill at drawing leads him into dangerous territory.

Alexander, a senior high school student with a passion and talent for comics, is going through a rough patch. His mother has been absent for years, doing good work abroad, leaving her son with the feeling that he has been deserted. His father is a manufacturer whose only concern for his son is to see him study business and join the family firm.

The boy’s resentment at their indifference to him and his anxieties along with his fear of abandonment, have been spilling over into the rest of his life, ending his relationship with Isabella when he reacts nastily to her announcement that she is going abroad to study.

Chance encounter

But he has two stalwart friends – his mentor Errikos, who runs a store that deals with collectors’ comics, and his classmate Philippos, a computer whiz. Later he also gets support from unexpected quarters when a chance encounter gets him into strife.

It’s his drawing that gets him into trouble and his drawings that might extricate him. Alexander is sketching a young man at a bar when he sees what appears to be an abduction. Two thugs escort a man away, at gunpoint – or don’t they? Alexander isn’t sure. And what is on the flash drive he finds in the matchbox that the young man flicked toward him with his foot just before the men disappeared?

Gutter takes its young hero into a world of unexplained deaths, disappearances and ruthless criminals. As his life at school and home deteriorates, Alexander investigates, using his artist’s skills of observation and a good dose of courage.

This novel is something of a novelty for Greek fiction. Attractive to both young readers and adults, it has a believable young hero and is set in the world of comics, which is still fairly new to Greece. There are many aficionados of comics, the author told Kathimerini English Edition, “but lots of people still believe they are trashy”.

She herself is a fan, and the book came out of “a combination of a love for comics and for this type of fiction”.

Papaliou reads a lot of comics and has attended many exhibitions on comics. Her favourites include some mentioned in the book – Persepolis and Maus – and her preference is for comics that deal with politics and history.

She was determined that the comics were to be part of the plot and not just the background.

When she was brainstorming the book, Papaliou explained, “I knew I wanted to write about a young person who was going through a crisis, and tell his personal story of neglect and loneliness along with the mystery. I thought, what if he sketches a mystery?”

Alexander identifies with the young man who disappears, and that takes him on his path of discovery.

Though she hasn’t specifically targeted young readers, the author says she would love to reach a young audience. She was attracted to the idea of writing about a young character. “I wrote it in the first person because then I could get his way of speaking across, in short sentences. It’s more action-oriented.”

One of Papaliou’s achievements in her novel is to portray a hero on the cusp of adolescence and adulthood – smart, with a passion for his craft, but held back by unresolved family and personal issues. We watch him grow as he boldly pursues the wrongdoers, and mellow as he comes to see that not everyone is against him.

It was a conscious authorial decision to show him facing the dilemmas and decisions that mark the passage to adulthood in the framework of this suspenseful tale. “I don’t think there are many novels that deal with young people deciding what to do with their lives”, commented Papaliou.

Kedros Publishers is launching Gutter at Papasotiriou bookstore (37 Panepistimiou St, 210.325.3232) at 7 p.m., on January 30.

The author

Dorina Papaliou was born in Athens. She studied History at Brown University and did postgraduate studies in Social Anthropology at Cambridge University. Her dissertation was on Karaghiozis and the magic of shadow theatre.

In addition to a work on oral narrative and its present-day revival, Papaliou has also written four books for children. Gutter is her first novel.

(Kathimerini)

By Sandy Tsantaki

Date of Publication: 18-12-2007

What do anthropology and comics have in common? Those who love Karaghiozis and shadow theatre can already see the connection in the name of Dorina Papaliou. Dorina Papaliou has compiled rare material on shadow theatre in a CD-ROM and very soon she will link her name with the first complete website dedicated exclusively to shadow theatre and its history (www.greekshadows.com). This time, the figures have changed. Having published four children’s books, the author releases her first novel starring comic artists and is entitled Gutter (Kedros Publishers). Rumour has it that it may soon be made into a film. We’d better rush and get a copy while we can…

– Why did you call it Gutter?

– First of all, for what it stands for, as a technical term also in Greek, in the comics jargon: the gap between two successive pictures, the space where the reader can mentally link one picture with the other, what comes before and what follows. The hero of my story, a budding comic artist, makes a sketch for no particular reason, which, however, spurs him to search for strange pictures of a complicated story that unfolds around it. However, “gutter” takes on another meaning in the story.

– Who did you have in mind when you were writing your novel?

– I wouldn’t limit its scope. The book has the structure of a crime novel, but tells the story of a young man who passionately struggles to achieve his life’s objective. In this context, it may very well appeal to the young, even to the very young.

– This is your first novel. Would you say that you and your heroes are “reaching maturity”?

– I wouldn’t place the children’s books that I wrote “prior to the novel”, but rather after a period of study in oral narrative, which led me to my book Listen to a Story: TheTraditional Art of Oral Narrative and its Revival Today (Akritas) and also the CD-ROM Karaghiozis: The Magic of Shadow Theatre (Kastaniotis Editions). I should say that they are both the outcome of my studies in social anthropology. Now I know that I wouldn’t want to stop writing books for children. Children are such a true, honest audience.

– What’s the best review you dream to receive? And the worst?

– I can tell you my second best! “I started the book in the evening and stayed up all night to finish it”. And the worst: “I had enough, I walked away halfway through it”.

(Eleftherotypia)

By Vena Georgakopoulou

Publication Date: 18-12-2007

The heroes of crime novels are usually police officers or detectives flirting with corruption (my apologies, Mr Charitos). Whatever came over Dorina Papaliou and she threw Alexander, an innocent, extremely polite child, into the hands of criminals? Didn’t she have any compassion for him?

“I wanted to write a novel in the spirit of the books I like to read,” says Dorina Papaliou about Gutter.” I didn’t think of it this way. I just thought it would be more interesting. After all, I wouldn’t want my hero to look like Highsmith’s Ripley, a wicked, lousy character”, replies the author of Gutter (Kedros Publishers). Apart from being the title of the young female author’s first novel, it is also a term from the world of comics. That’s home to 18-year-old Alexander Damianos – an upper class high-school student – until he is forced not to abandon it, but useits weapons to solve a crime.

A crime novel wasn’t quite what we had expected from Dorina Papaliou. She was known for her four illustrated children’s books, a magnificent CD-ROMon Karaghiozis and an essay on the traditional art of oral narrative. She caught us by surprise, and a pleasant one, too. You don’t have to be an avidcrime fiction fan to devour Gutter. In this context, she is not taking her first tentative steps in a particular literary genre, but making an entry into literature.

– Would you say that Gutter is, in the first place, a book for teenagers or a crime novel whose hero happens to be in his teens, in the sense that he might as well be a middle-aged police officer? In other words, what was your primary objective, the genre of the recipients?

“It was my intention to write a book in the genre of crime fiction. I started out with the idea of a young comic artist who, because of his acute perceptiveness and his obsession to make sketches all the time, unwittingly got himself into deep trouble by accidentally sketching a scene of a crime. The fact that the hero is 18 years old resulted in the course of things, as I was piecing together the private life of the hero in Gutter. The dilemmas and difficulties confronting the very young, the passage to independence, the moment you take your life in your own hands, seemed to me to be much more fitting for the central character than an established professional. Besides, the world of comics is full of young people. Alexander’s anti-conformist character, his feelings and anxieties are intimately linked with his weird and haunting passion to seek out the truth behind a story, that a sketch sent rolling. In this respect, I would say that the reason I chose an adolescent hero was for the sake of his personal story and the role of comics in the plot. As for the audience it is directed at, thescope is unlimited”.

“Personal quest”

– Why was your first novel in the crime genre?

“I adore crime fiction, the classic and noir authors, as well as the more modern ones, like Mankell, Dexter, Pears and Donna Leon. As for the earlier generation of Greek authors, Yiannis Maris is my favourite, while P. Markaris stands out among contemporary ones. In a sense, I wanted to write a novel inthe spirit of the books I like to read. On the other hand, Gutter is not the type of crime novel featuring a police officer or detective investigating a case in the context of a professional doing his job. It incorporates a personal story, concomitant with the crime storyline, a personal quest, what a young man does with his life”.

– He seems, however, to have all the right qualities to undertake similar missions in the future. Will you let him?

“As far as I am concerned, Alexandros will always be a child drawing comics, who just happened to get involved in a dangerous mission atsome point in his life. I’d rather have new characters in my next book”.

– What other qualities, apart from literary ones, did you realize that a crime fiction author should have?

“When I started writing Gutter,I knew exactly what I wanted to happen, to whom and why, as well as how the story would end. However, exactly how all these elements would fit together, turned out, in the course of things, to be considerably more difficult than I had imagined and so I ended up working on the book for two years. What proveduseful, and would also be a suitable first step next time I embark on a novel, was a particularly detailed summary”.

– You seem to be familiar with the hangouts and habits of a certain class of young people. Where did you draw your material from?

“From conversations and research – I read a lot of biographies, books about the history and technique of comics, interviews with comic artists – and, naturally, did my rounds incontemporary Athens, what in filmmaking is called ‘repérage’: the search for areas where the characters in the story dwell: the districts of Athens that Idon’t frequent, the routes taken by Alexander, if he were a real person”.

“Biology and history”

– History, social anthropology, Karaghiozis, children’s books. Do you feel that with Gutter you have reached a destination, namely literature, where you should stay on?

“Eighteen was a difficult age for me, unlike my hero, who has a crystal clear picture of what he wants to do in his life. When I went to university in the U.S.A. I had originally declared marine biology as my major. In my first year at Brown University, however, I attended classes in the Department of Neurobiology, because it seemed like the most interesting thing for me at the time. In my first summer, I worked in the Department of Neurology of University College, London, where I watched, for the first time, experiments on animals. I could not bear it. In my second year, I changed my major to History. But it wasn’t a last resort solution. I found it extremely fascinating in a way quite different from that of biology. Parallel to this I took classes in film directing, script writing and creative writing. America opened up a lot of opportunities for me and during the four years of my stay there helped me to realize what I really wanted to do with my life. My graduate studies in social anthropology were one more opportunity to explore the route I had opened up. And so today, I can confidently say that I have found what I really want to do, which is only to write”.

– You are married to well-known author Apostolos Doxiadis. Can two authors fare well under the same roof?

“I should say that we get on very well together. We have much in common; we can talk for hours and are aware of each other’s concerns. I’ve been married to Apostolos since I was 23, and I wouldn’t want to know a different life. The best part of it all is that, in the evenings, we can both tell good stories to our kids”.